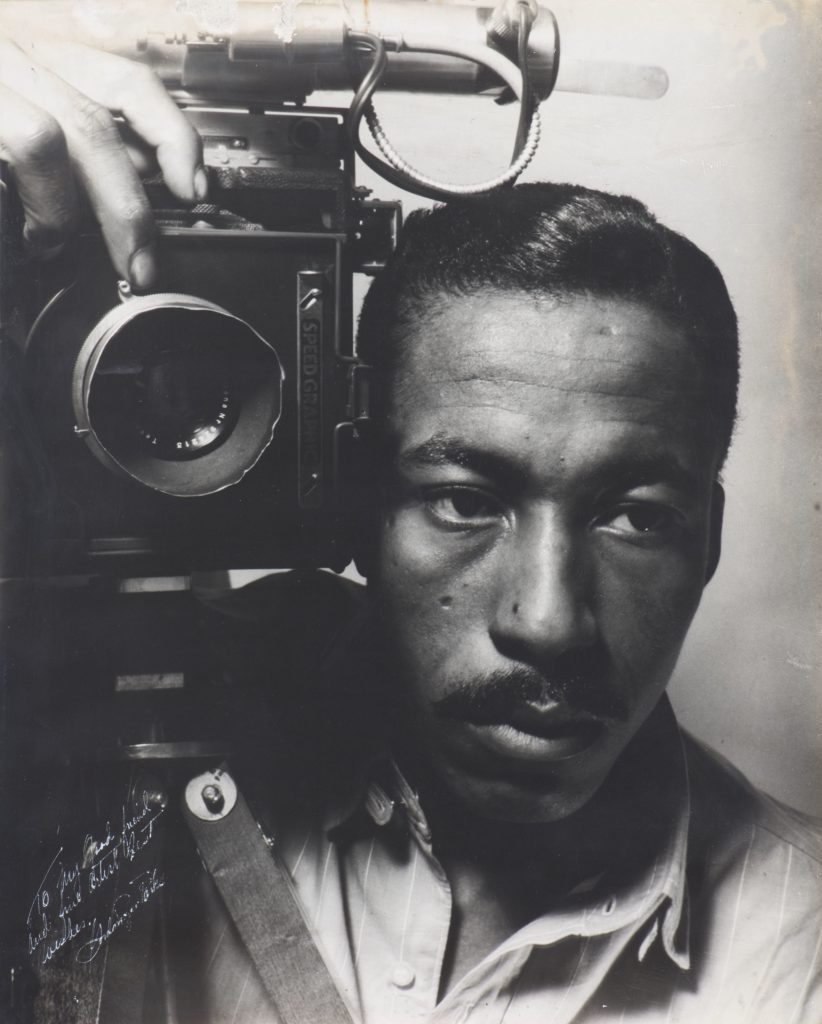

To call Gordon Parks one thing would be an impossibility.

Over the course of his life, Parks was a poet, novelist, jazz pianist, classical composer, an accomplished photographer who was the first Black photographer at Life Magazine as well as an editor for Essence magazine of which he was a co-founder and the first African-American director of a major Hollywood movie, “Shaft.” He also wrote the screenplay for that movie, which was based on a semi-autobiographical book that he wrote called “The Learning Tree.” Parks also helped jumpstart blaxploitation cinema in the early 1970s with the iconic film “Shaft.”

Though, it would be fair to say that, despite all of this, he is relatively unknown outside of certain circles. His name doesn’t loom large over history, despite his influence and the things he showed us about a divided America looming heavily on our current world.

Parks was born in rural Kansas in a town that straddles the Missouri border called Fort Scott. The youngest of 15 children, his father, Andrew Jackson Parks, was a farmer. He attended a segregated elementary school, and though his high school was segregated, Black students weren’t allowed to play sports or attend extracurricular activities.

When he was 11 years old, three white boys threw him into the Marmaton River, believing he couldn’t swim. He had the presence of mind to duck his head underwater so that the boys wouldn’t see him swim to the shore.

At 14, his mother, Sarah Ross, died and he spent the last night in his childhood home next to his mother’s coffin. Shortly afterward, he went to live with his sister and her husband in St. Paul, Minnesota, but he fought with his brother-in-law and was turned out. He worked odd jobs for some time until finally, on a trip to Seattle, with 12 dollars in his pocket, he bought a camera, a Voigtländer Brilliant for $7.50.

Eventually, Parks landed a job with the Town and Country Department Store in St. Paul, Minnesota, and worked there for years as an official photographer. He worked for local newspapers and documented life on the south side of Chicago. For this, he won a Julius Rosenwald Fellowship in 1941, eventually being hired by the Farm Security Administration (FSA), a government organization formed by the New Deal that was created to document poor, rural workers living in America in order to bolster support for government aid.

It was in the FSA that Parks took perhaps his most famous photo. A black and white photo with subject Ella Watson, an African American mother and worker. A broom in one hand, a mop in the other, and behind her just above her right shoulder hung an American flag. In the photo, her face looks off to her right just slightly, forlorn, tired and perhaps with a bit of confusion as to what’s happening.

After viewing the photo, the head of the FSA Roy Stryker said that it would get them all fired.

“He said, well, you’re getting the idea but you’re gonna get us all fired,” said Parks about Stryker’s response. “This is a government agency and that picture is an indictment against America.”

The photo, “American Gothic, Washington, D.C.” takes its name from the Grant Wood painting of a farm couple with a pitchfork. Parks’ rendition expressed, for many, the lie inherent in the “American Dream” for the poor and destitute working class of America, especially for African Americans.

“I felt the need for me, somehow or another, to use humanity to get people to become aware of how people suffered,” said Parks of his time working for the FSA. “That was what drove me into it, to expose to the public something that I thought was being hidden.”

In Parks’ autobiography, he would claim that the photo was “unsubtle.”

“I overdid it, and posed her, Grant Wood style,” wrote Parks, describing his conversation with the woman who told him about her life and how when she worked long, arduous hours, “different neighbors” would watch her children.

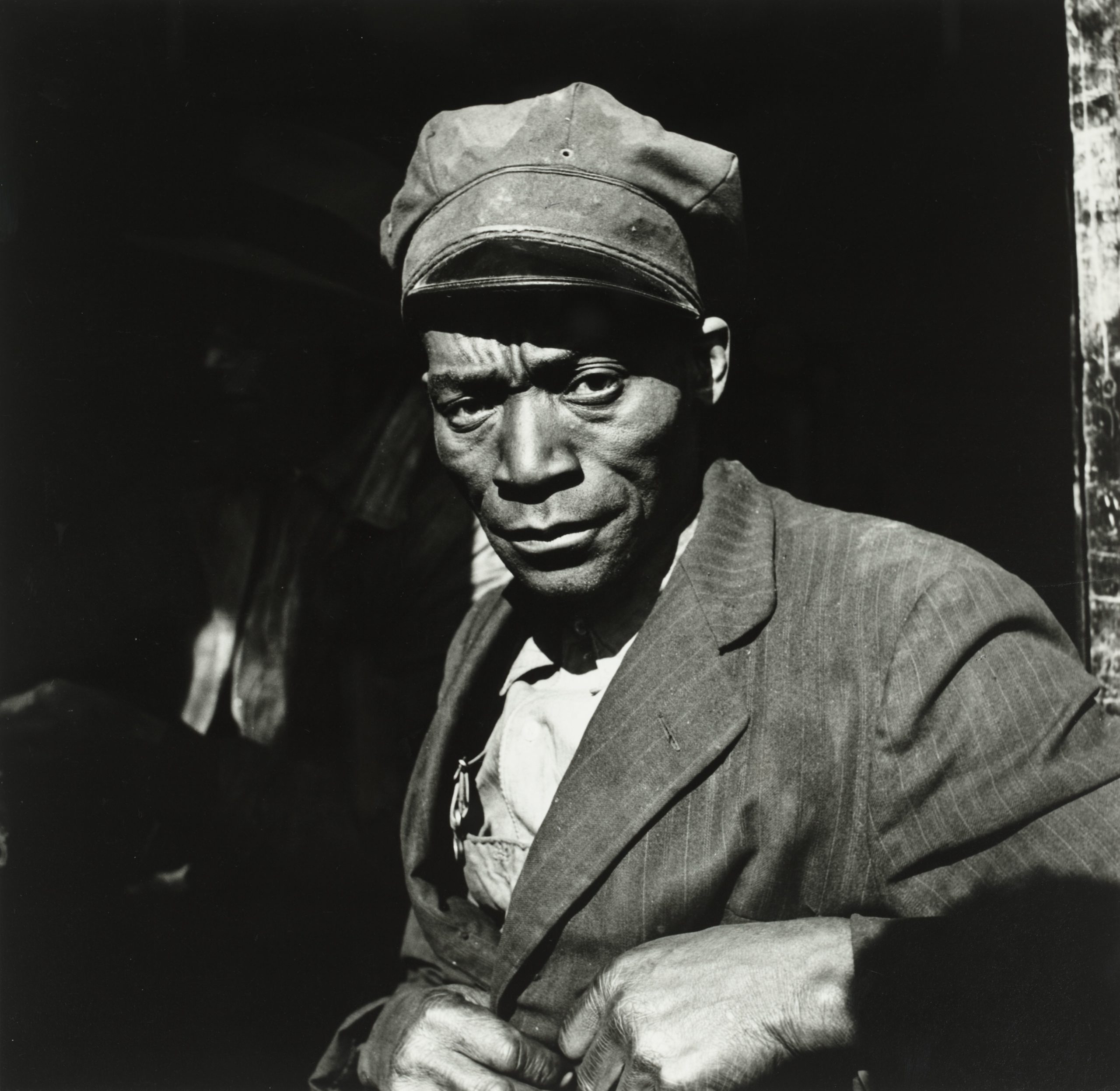

Parks’ photography showed hardship, an insight into lives that were, at that time, hidden; not just of the working poor but of a side of the world that, up until that point, had been hidden. He showed what life was like, on a grander scale, what it was like for the African American community in a pre-Civil Rights world.

Shortly after capturing Ella Watson’s photo, Parks worked on a photo essay for Life Magazine. The essay followed Leonard “Red” Jackson, a 17-year-old leader of a Harlem gang, called “The Midtowners.”

The lead photograph features Red hiding from a rival gang in an abandoned building, a broken window before him. He is surrounded by darkness, the only light shining in through the window, a cigarette in his mouth as he waits and stares out.

It is revealed several pages later that Red was on his way home from a funeral of a friend, a 15-year-old named Maurice, who was found dead on a Harlem street. The cops, who had found the boy’s body, had determined that the boy’s death was accidental, mirroring the many instances before and afterward where similar “accidental deaths” had been determined by the police.

The entire photo essay illustrates the rough life of Harlem youth in the 1940s, but what it leaves out are the photos that showed Red and his fellow gang members living their lives, attempting to be simply that: kids.

In 1956, Parks went to Alabama to photograph segregation in the south, some of which are among his most famous photographs. A few of them are paid homage in the first episode of the HBO series “Lovecraft Country.”

He captured a wealth of photographs of people living their lives in quiet dignity as the reminders of society’s cruelty hung over their heads in signs that read “Colored Waiting Room” or “Colored Entrance.”

Parks captured people as they were, living their lives. In doing so, he implicated the viewers of his photographs. He showed them people who deserved understanding, sympathy and a right to live and breathe as their neighbors live and breathe. Parks’ photos showed Americans what they refused to see for themselves, the cruelty they allowed because they didn’t have to look at it. Parks made people look and empathize.

“I pointed my camera at people, mostly, who needed someone to say something for them and couldn’t speak for themselves,” said Parks.

Richard Foltz

Associate Editor