The first recorded case of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was discovered in 1983. Since then, scientists have made strides in slowing down the disease and making medical advances that ensure a healthy life for those affected by it.

However, a new breakthrough has been made by Dr. Kamel Khalili, chair of Temple University’s department of neuroscience, and Dr. Howard Gendelman, an infectious disease and pharmacology researcher at the University of Nebraska.

On July 2, 2019, researchers from Temple announced that they had combined an experimental long-acting HIV therapy with a gene-editing technique to eliminate the virus from the genetic code of about one-third of treated mice. It is the first time the virus has been eradicated from a living animal.

Khalili and Gendelman combined two methods of HIV treatment to obtain the results of their latest research.

Most treatment of the virus uses antiretroviral therapy (ART), which suppresses the replication of HIV to levels that make it undetectable in a person’s bloodstream.

ART alone, however, isn’t a cure for the virus, as it is only a suppressant. It requires lifelong use to keep the HIV cells from replicating and developing acquired immune deficiency (AIDS) over the course of months and years.

Khalili’s team use Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR-Cas9) technology to develop a gene editing and gene therapy delivery system to remove HIV DNA from human genomes harboring it. This is how the virus was removed from the test mice. However, it is not a permanent solution either.

In the new study, Khalili used CRISPR-Cas9 in tandem with Gendelman’s newly developed method of long-acting slow-effective release (LASER) ART.

LASER ART is different from normal techniques, as it exclusively targets sanctuaries of the virus and keeps replication of HIV at undetectable levels in the blood for much longer, reducing the need to medicate a patient frequently with ART.

This was accomplished by changing the chemical structure of the antiretroviral drug, packaging them into nanocrystals. These nanocrystals are then distributed to tissues that are most likely to have dormant sanctuaries of HIV.

The nanocrystals are stored inside cells for weeks, triggering slow and prolonged ART action where it counts.

“We wanted to see whether LASER ART could suppress HIV replication long enough for CRISPR-Cas9 to completely rid cells of viral DNA,” Khalili said, explaining the goals of the study.

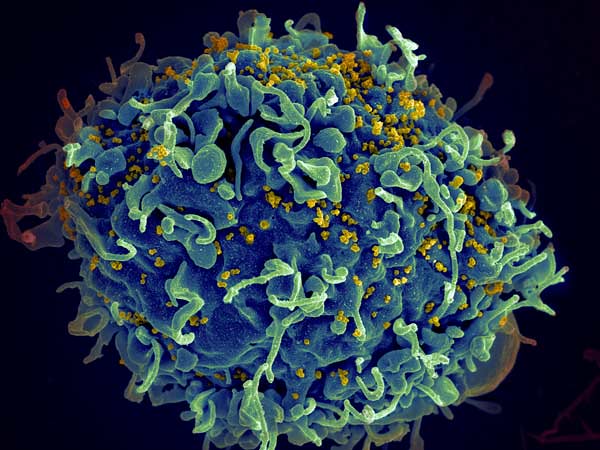

The researchers used mice engineered to produce human T cells susceptible to HIV infection, permitting long-term viral infection.

The mice were treated with LASER ART to suppress the virus and then CRISPR-Cas9 to eliminate the dormant virus from affected cells.

Following treatment, the mice were examined to see if the virus was still present, and one-third of the infected mice had the HIV DNA completely eliminated.

While seen as impressive, the CRISPR technology is only eight years old, and technical and ethical questions remain about the ability to precisely edit genes.

The University of Pennsylvania launched the first use of CRISPR on humans in the U.S., as it engineered immune cells to fight certain cancers.

A full-fledged cure for HIV is still years away, but these developments are the most significant in a long time.

Khalili looks to the future, as he plans to continue tests to optimize the combination of virus suppression and gene editing. The next steps are to begin testing the procedure on nonhuman primates.

“The big message of this work is that it takes both CRISPR-Cas9 and virus suppression through a method such as LASER ART, administered together, to produce a cure for HIV infection,” Khalili said. “We now have a clear path to move ahead to trials in non-human primates and possibly clinical trials in human patients within the year.”

Henry Wolski

Executive Editor