This past Wednesday was Juneteenth, the most popular celebration of emancipation from slavery in the U.S. The holiday stems from the events of June 19, 1865, when Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger rode into Galveston, Texas, proclaiming that slaves are free.

Granger advised the freedmen to stay at their present homes and work with their former owners as employees and be paid a wage for their labor.

This announcement came two and a half years after the Jan. 1, 1863 Emancipation Proclamation by Abraham Lincoln.

Several theories have been brought to explain the long delay, one of which being that the original messenger of the news was murdered on route to delivering the news. Another claims that the news was deliberately withheld by slave owners in order to reap the benefits of one final cotton harvest before enforcing the law.

The most likely reason is the Proclamation itself wasn’t enforceable in states on the Union-Confederacy border or southern states that hadn’t been captured by the Union, such as Texas until the end of the civil war. Before its end, Lincoln and the Union would have no jurisdiction over those areas.

A number of freedmen found the idea of continuing to work with their former masters (that kept them in poor living conditions, beat them and treated them like property) unfavorable to say the least, and instead chose to flee to the north.

This was called “the scatter” and in addition to seeking refuge in northern states, freedmen also left in search of family members that they had been separated from.

The freedom process wasn’t immediate, as the news was slow to spread in Texas, one of the largest states in the nation. Slave owners would also refuse to comply with the order, sometimes lynching, beating or murdering freedmen trying to escape their captivity.

Adding to this was the rolling out of laws that started the process of segregation and kept slavery alive in other ways, such as Jim Crow and sharecropping.

Despite this, the 250,000 freed slaves of Texas persevered and began the long process of acclimating themselves into society and fighting for true equality.

One year later in 1866, the freedmen celebrated the first Juneteenth. There are accounts of them tossing their ragged garments into creeks and rivers, and taking clothing from their former masters. This is due to laws that prohibited or limited the dressing of the enslaved. The freedom to dress how they please was not taken for granted.

“The way it was explained to me, the 19th of June wasn’t the exact day the Negro was freed,” said one of the first celebrators of the holiday, in an essay from historian Elizabeth Hayes Turner.

“But that’s the day they told them that they was free … And my daddy told me that they whooped and hollered and bored holes in trees with augers and stopped it up with [gun] powder and light and that would be their blast for the celebration.”

The freedmen ran into problems at first, as segregation laws were already being passed and there were no public places that would allow them to gather.

In the 1870s, former slaves would pool together $800 and purchase 10 acres of land that they christened “Emancipation Park.” It stood as a bastion of hope for African Americans, as it was the only public park and swimming pool in the Houston area that was open until the 1950s.

Juneteenth would continue to be celebrated, with its popularity crossing Texas lines and becoming nationally known. As Texan freedmen moved out of the state, so did their traditions.

However, the holiday diminished a bit in the late 1800s and early 1900s, with the implementation of Jim Crow laws and other slights against African Americans. They felt a disconnect from their history.

During the civil rights movement in the ‘60s, driven by the strides made to expose and extinguish segregation, African Americans brought Juneteenth celebrations back, when the Poor People’s March planned by Martin Luther King Jr. fell on that fateful date.

With this renewed energy, Texas passed a bill in June 1980 making Juneteenth an official holiday of the state. Rep. Al Edwards of Houston was the brain trust behind the measure and framed the holiday as a source of strength for young people, according to Hayes Turner.

Several organizations and websites were commissioned following this to observe Juneteenth and make it a federal holiday.

“We may have gotten there in different ways and at different times,” Rev. Ronald Meyers, founder and chair of the National Juneteenth Observance Foundation said. “But you can’t really celebrate freedom in America by just going with the Fourth of July.”

Little by little, more states established Juneteenth as an official holiday, with Pennsylvania being the most recent to do so last week. As of this writing, 46 states observe the holiday.

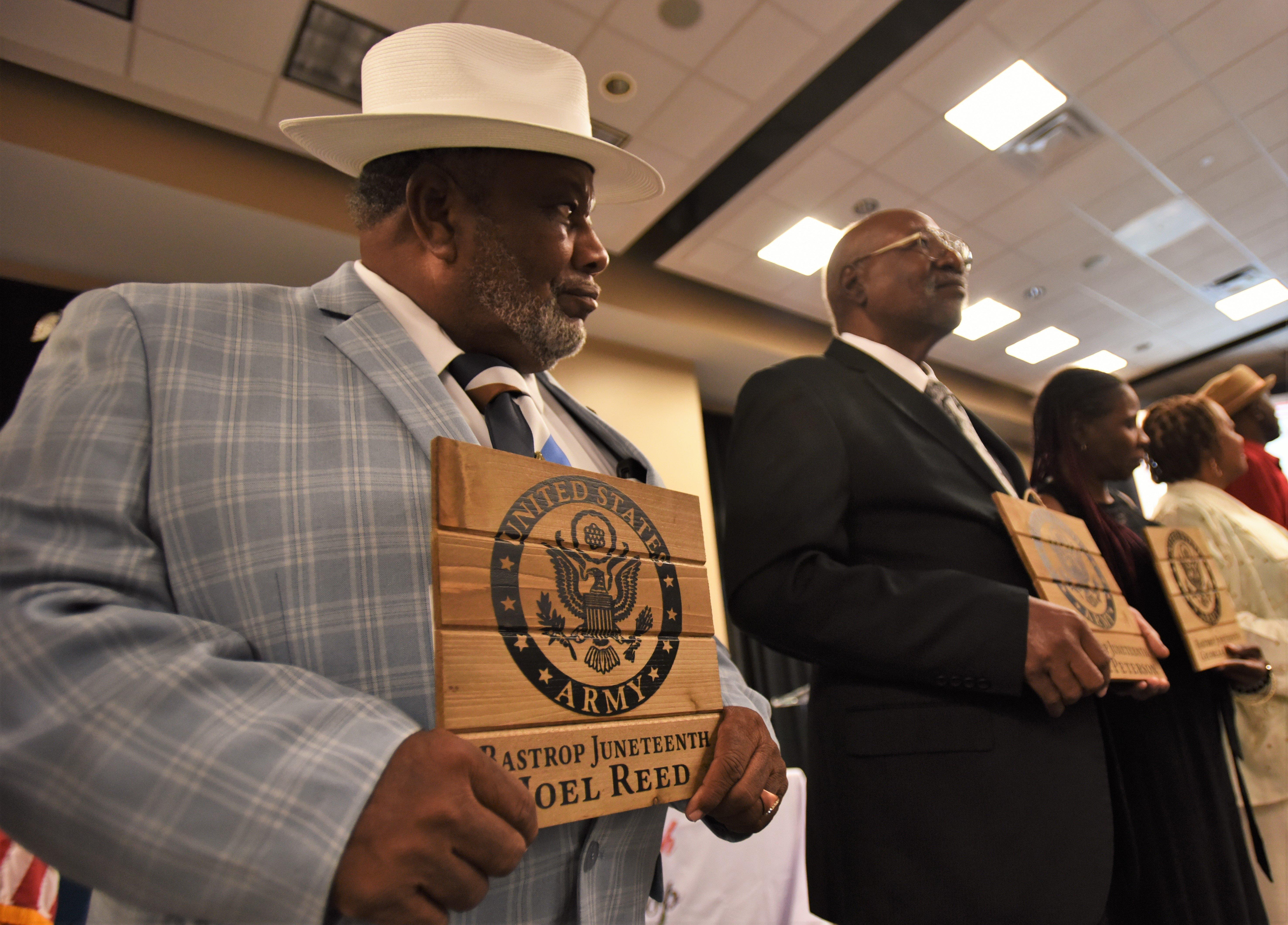

Despite not being a federal holiday, Juneteenth is celebrated across the nation with an emphasis on history, education, self-assessment, self-improvement and planning for the future. Celebrations are often characterized by concerts, contests, picnics and parades.

It is celebrated differently depending on where you are, as southern states celebrate with oral histories, readings and barbecues, while rodeos are a common event in the southwest.

The Marcus Garvey bean salad, a mix of red, green and black beans, is a staple of Juneteenth festivities. It is a tribute to Garvey, a famed black nationalist and the color of the beans represents the African nationalist flag.

Another food with historical connotations is the Kente cloth cake, based on the multi-colored fabric originally worn by the king of the Ashante people of Ghana, West Africa. It is more common nowadays but is still considered an important and royal fabric.

“In cities across the country, people of all races, nationalities and religions are joining hands to truthfully acknowledge a period in our history that shaped and continues to influence our society today,” juneteenth.com states. “Sensitized to the conditions and experiences of others, only then can we make significant and lasting improvements in our society.”

Henry Wolski

Executive Editor