This is an extended version of the article found in the 26th edition of The Clarion. Enjoy 500 extra words about the story of Charles “Boss Ket” Kettering. We can’t always fit entire articles in the print edition, so be on the lookout for the most current and detailed versions of stories here on our website.

In the early 1900’s the city of Dayton was a mecca for inventors and patents. By 1903, it was the U.S. city with the most patents per capita.

There have been many individuals who have made their mark on Dayton and overall history with their creations, including the Wright Brothers with the invention of flight. Common conveniences we use every day, like the ice cube tray, the pop tab and the search engine, were all invented in Dayton. These things will be what we look at in the last few Gem City History installments this semester.

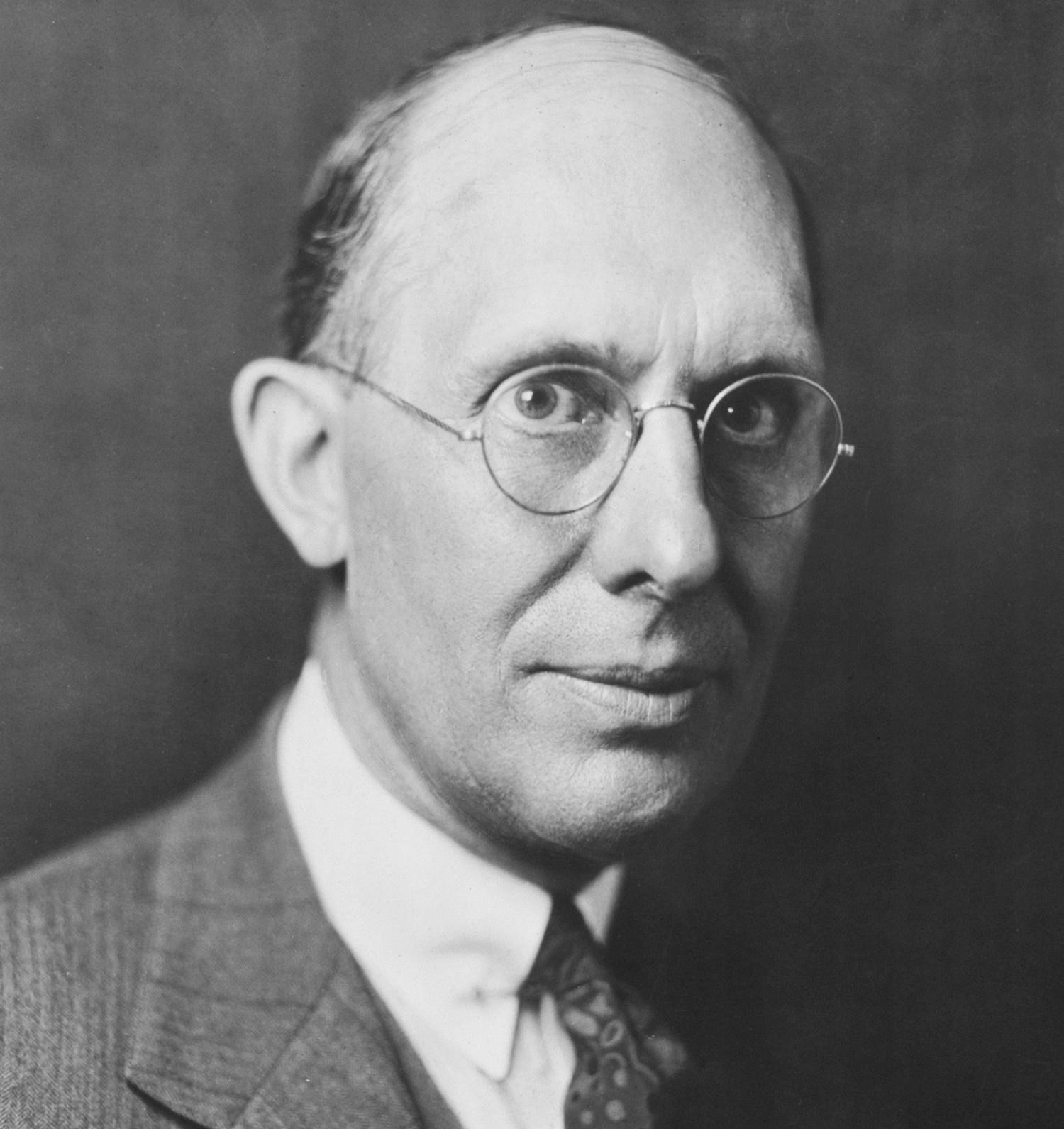

Yet maybe the most prolific Dayton inventor was Charles F. Kettering, who was born in Loudonville Ohio in 1876. He graduated from Ohio State University in 1904 with a degree in electrical engineering, which he put to use immediately after graduation by being hired to work at NCR.

He was the head of research there, and helped start a simple credit approval system, similar to a credit card, as well as inventing the electric cash register in 1906, making ringing up sales easier for clerks.

One of Kettering’s philosophies was being a practical inventor. He once said, “I didn’t hang around much with other inventors and the executive fellows. I lived with the sales gang. They had some real notion of what people wanted.”

In his five years at NCR he secured 23 patents for the company. He attributed his success to a decent amount of good luck but stated, “I notice the harder I work, the luckier I get.”

During his time there, he was convinced by a colleague from NCR, Edward A. Deeds, to develop innovations for automobiles.

Deeds told Kettering that “there is a river of gold running past us,” referring to the booming automobile industry. The two invited other NCR engineers to join them, and they spent their nights and weekends working in Deed’s barn. This christened them as the “Barn Gang,” led by Kettering, who was called Boss Ket.

One of the first successful inventions made by the Barn Gang was an improved ignition system, which expanded the life of automobile batteries. They presented the device to companies, who showed interest.

Kettering then resigned from NCR in 1909 to concentrate on the automotive industry. He and others from the Barn Gang created the Dayton Engineering Laboratories Company, or Delco.

Perhaps his biggest invention was made there: the electric self starter. Before Kettering’s invention, cars had to be started by using a hand crank. Sometimes the crank would act up, and kick back and hit the operator, usually causing injuries like broken arms, wrists or shoulders.

It became more serious however, when a man named Byron Carter cranked the engine for a stranded driver near Detroit Michigan, and had his jaw broken by a crank kickback. Due to complications, he later died of pneumonia.

After this, the chief of Cadillac Henry M. Leland sought out Kettering to help create an electric starter. Leland’s team had made one, but it was too large for practical use.

Delco employees work vigorously and finished the starter in February 1911. Kettering and his team were passionate and knew the importance of the job, with him saying at one time that they didn’t have a job so much as the job had them.

Using his knowledge in electrical engineering, Kettering was able to make the device fulfill the three purposes it still serves to this day: starting the car, and working as a generator, that produces the spark needed for ignition and the current for lighting.

Leland approved the product for the 1912 Cadillac model and ordered 12,000 self starters from Delco. This essentially put the company on the map and caused an expansion to handle the demands of large scale production, as it was previously primarily focused on research and development.

Delco’s work on the starter earned Cadillac the Dewar Trophy in 1912. The Dewar trophy is donated every year by a U.K. group called the Royal Automobile Club to “the motor car which should successfully complete the most meritorious performance or test furthering the interests and advancement of the [automobile] industry.”

In 1916, he would sell Delco to United Motors, which was later sold to General Motors (GM) two years later. It would become the foundation for the GM Research Corporation. Kettering became vice president of GM Research Corporation in 1920 and held the position for 27 years.

In 1916, he would sell Delco to United Motors, which was later sold to General Motors (GM) two years later. It would become the foundation for the GM Research Corporation. Kettering became vice president of GM Research Corporation in 1920 and held the position for 27 years.

At GM, he continued researching and finding new innovations for the auto industry. Kettering spent much of the time researching on fuel and through his practices increased the octane rating of gasoline. One of his experiments involved mixing ethanol with gasoline, a practice still used today.

One area where he mistepped was hiring Robert A. Kehoe as a medical expert that proclaimed leaded gasoline was safe for humans. However, its use led to disaster with global lead contaminations that would not come to light until long after Kettering’s time.

He also helped develop diesel fuel engines, and worked to find ways to harness solar powers in automobiles.

Another Kettering invention happened in 1918 when he designed a 300 pound papier-mache missile called the Kettering Bug. It had 12 foot cardboard wings, a 40 horsepower engine and could carry 300 pounds of high explosives. It is considered the first aerial missile, and further research led to the development of the first guided missiles, as well as radio-controlled drones.

His efforts earned him a spot on the cover of TIME Magazine in January 1933, with the story focusing on the strides made in the auto industry, with GM leading the charge.

Kettering’s way of thinking was different than most of his contemporaries. He believed that calculations based on theories were invalid, since they were the limits of experience, not possibility. He was a go getter who encouraged those under him to solve problems completely, instead of making the problem less bad.

One of his famous quotes is “It doesn’t matter if you try and try and try again, and fail. It does matter if you try and fail, and fail to try again.”

Max D. Liston, one of Kettering’s co-workers at GM, described him “one of the gods of the automotive field, particularly from an inventive standpoint.” Liston quoted Kettering as advising him, “People won’t ever remember how many failures you’ve had, but they will remember how well it worked the last time you tried it.”

Following the TIME cover story and other media appearances, Kettering’s fame started to grow. However, it didn’t matter much to him, as he dressed casually, didn’t carry cash on him and drove a low-end Chevy to remain inconspicuous. Yet wealth and fame would take Kettering to new avenues

In 1945, he founded the Sloan-Kettering Institute for the study of cancer. He was a major advocate of medical research and applied the same methods from his engineering experience to the medical field. His wife, Olive Kettering would pass away from cancer the following year, which only fueled his interest in finding a cure for the disease.

He was a benefactor of Antioch College, near Yellow Springs, and was a fan of their work-a-term, study-a-term program.

He then retired from GM in 1947 at the age of 71, and spent his time relaxing and going on public speaking tours, focusing on research, progress and education. A common theme of many of his speeches was failure and how to deal with it.

He then retired from GM in 1947 at the age of 71, and spent his time relaxing and going on public speaking tours, focusing on research, progress and education. A common theme of many of his speeches was failure and how to deal with it.

In this quote he speaks of the way different industries interpret failure:

“I think it was the Brookings Institution,” he said, “that made a study that said the more education you had the less likely you were to become an inventor. The reason why is: from the time a kid starts kindergarten to the time he graduates from college, he will be examined two or three or four times a year, and if he flunks once, he’s out. Now an inventor fails 999 times, and if he succeeds once, he’s in. An inventor treats his failures simply as practice shots.”

Kettering passed away in 1958, but left behind a legacy of invention and excellence. He owned over 140 patents to his name (the only person to have more is Thomas Edison). His contributions to the city of Dayton are vast and too much to mention here.

Now, reminders of what he did are everywhere. The cars we drive were able to improve because of his self starter technology. Colleges, a system of hospitals and medical centers across the city, six schools, the engineering building at the University of Dayton and an entire suburb bear his name to commemorate his impact on the Gem City.

Henry Wolski

Executive Editor