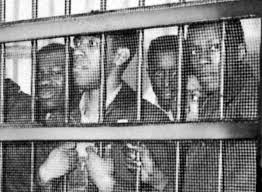

On January 31, 1961 the Friendship Nine group went to jail for an anti-segregation protest. These African American men returned to court in 2015, fifty-four years later, to find out that the State of South Carolina would clear their criminal records, as well as their charges filed against them.

On January 31, 1961 the Friendship Nine group went to jail for an anti-segregation protest. These African American men returned to court in 2015, fifty-four years later, to find out that the State of South Carolina would clear their criminal records, as well as their charges filed against them.

“We cannot rewrite history, but we can right history,” said the judge, John C. Hayes III, the chief administrative judge for South Carolina’s 16th Judicial Circuit.

“Now is the time to recognize that justice is not temporal, but is the same yesterday, today and tomorrow.”

The men of Friendship Nine went to jail after they joined a staged sit-in at a segregated lunch counter in Rock Hill, South Carolina. This happened right at the peak of the civil rights movement.

At the time, Robert McCullough, John Gaines, Thomas Gaither, Clarence Graham, Willie Thomas Massey, Willie McCleod, James Wells, David Williamson Jr. and Mack Workman were students of Friendship College and active protesters protesting against segregation rules. The group of nine were denied service when they walked into McCrory’s, and when they were asked to leave, they refused, which resulted in them being arrested.

Graham said they spent months planning to enlist in the civil rights movement across the South.

“We just got tired of being second-class citizens,” Graham said. “We were often kicked, spit on, cursed out.”

According to NPR, it was a quiet act of defiance, met with violence.

“I remember being grabbed up by my belt and thrown to the floor and dragged out of the store,” Graham said in an interview with NBC News.

McCleod said he was afraid because the policemen were lined up grabbing several people to arrest them.

“It was a frightening experience, but the part that got me is when they put me in the cell and closed that door. And that clang, you can still hear it,” Williamson said.

The group members said they were put in the cells to await their charges, and felt as if the police was treating them poorly on purpose.

“They wanted to give us the

kind of treatment they thought we deserved,” Wells said. “They didn’t care.”

Rather than the Friendship Nine group paying a fine because of their actions during the 60s, they chose a different alternative: “Jail, no bail.” They were sentenced to hard labor, and convicted of trespassing.

This alternative became a strategy that breathed new life into the civil rights movement, according to NBC News. The Friendship Nine was the first participants to insist on actually doing their time, instead of paying the fine.

According to activists groups, bailing out protestors was becoming an issue because civil rights groups were running out of funds. Professor Adolphus Belk Jr. of Winthrop University said this strategy rescued the civil rights movement.

“Rather than assuming the financial responsibility of paying that fine, it shifted to the system,” Belk said. “I suspect if the Friendship Nine didn’t do what they did in January, 1961, the sit-in movement would have died.”

As a result of their decision, the group was sentenced to 30 days of hard labor at the county prison farm, which consisted of moving large sand piles and cement blocks, pulling weeds and working on private farms.

Williamson Jr. said it was a hard 30 days in prison, but not as hard as carrying out the conviction for 54 years. He said it was like a chain dragging behind him.

“You always had it back there in the memory, and any time you would fill out an application you always had to tell them and you wondered if it would affect if you got the position or not,” Williamson Jr. said.

Massey said they felt as though that they served their time, and thought of it as a badge of honor.

“I think all of us realized that we had tapped onto something; I think it was a badge of honor,” Massey said.

According to NBC News, the group had no idea how much their decision would effect the nation.

“At the time, we didn’t know how important it was, but as you look back, you realize it was a turning point for the movement,” Williamson said. “We were in the right place at the right time to the right job,” Massey added, in an interview with NBC News.

Three years ago, children’s author and Rock Hill native, Kimberly P. Johnson, said it’s important that justice be made right for these men.

According to Johnson, the group simply wanted freedom—that’s what made them protest. She said it wasn’t just about the right to sit down and eat where they would like, but also just to walk down the street knowing they had freedom without being cursed at.

Once Johnson brought attention to the Friendship Nine case, she went to Rock Hill solicitor, Kevin Brackett to erase their unjust conviction.

“What these men did wasn’t wrong, in fact it was right. And what they did wasn’t illegal, it was an act of principled courage,” Brackett said.

Brackett presented their case in court by arguing their conviction was based completely on their skin color, which would never stand in today’s society.

“I’m giving them back what they are entitled to, which is their dignity and their ability to say ‘I broke no laws,’” Brackett said.

Johnson said these men are great role models for children today because of their belief in non-violent protests. She said it’s a great message because it shows that justice does find a way back.

McCleod said he would do it all over again because it was something that needed done.

“It made a big difference in the civil rights movement, also in humanity, so I’m very proud of it,” McCleod said.

Gabrielle Sharp

Executive Editor

- Fri. Apr 11th, 2025