Martin Luther King Jr., originally born Michael, was born on Jan. 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia. His family was middle-class and King was well-educated as a child. At a young age, he felt the effects of racism. King had a memory from around the age of six of a white child saying that his parents had started to send him to a segregated school, and now forbade him from interacting with King.

King also had a strong dislike for violence at a young age. Whether it came from a schoolmate, his brother, or a white woman who slapped him and accused him of stepping on her foot, King never fought back.

When King was only 12-years-old, he suffered the loss of his grandmother to a heart attack. King had been at a parade, without the permission of his parents, when he heard what had happened. Distraught, King tried to jump from a window on a second-story level to attempt suicide.

However, King bounced back and went on to complete high school in two years. In 1944, he went to a tobacco farm in Connecticut and worked there the summer before starting college. King found that life up North was much different compared to where he was from. While his work conditions could be harsh – working outdoors all day where temperatures could get high – King was paid $4 for a day’s worth of work, which was a much larger amount than what he would have been paid in the South. He also found that blacks were not prohibited from going places in the North. He was able to attend the same church as white people. He shared his positive experience at a restaurant with his mother through a letter :

“Yesterday we didn’t work so we went to Hartford,” he wrote. “We really had a nice time there. I never thought that a person of my race could eat anywhere, but we ate in one of the finest restaurants in Hartford.”

Returning to the South was hard for King after his time in the North. While he was able to travel as he pleased part of the way home, he was forced to take a segregated train once he reached Washington, D.C.

“After that summer in Connecticut, it was a bitter feeling going back to segregation,” King said in his autobiography. “I could never adjust to the separate waiting rooms, separate eating places, separate restrooms, partly because the separate was always unequal, and partly because the very idea of separation did something to my sense of dignity and self-respect.”

King began to attend Morehouse College in Atlanta fall of the same year when he was just 15-years-old. Originally, he had shown an interest in the law and medicine, but he later decided to be a minister, following the footsteps of his father. During his time at the college, King was mentored by Benjamin Mays, the school president, who was dedicated to the fight for racial equality. Mays encouraged blacks to take part in this fight, leaving a large impact on King.

In 1948, King graduated from Morehouse with a Bachelor of Arts in sociology. He then attended the Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania. At a school composed mostly of whites, King was elected president of the student body. He graduated from Crozer in 1951 with a Bachelor of Divinity degree.

King started to attend Boston University that same year, where he had a focus on philosophy and ethics. He graduated from the school in 1953 with a doctorate in systematic theology. King also met his wife, Coretta Scott, in Boston. They married in 1953 and had four children together.

On Dec. 5, 1955, King took part in the Montgomery Bus Boycott in Alabama, where he had been serving as a minister at a church. After Rosa Parks had been arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a bus to a white person, blacks planned to boycott the bus system. Over 40,000 blacks joined in, resulting in a boycott from about 75% of the system’s riders. They came together to create the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) and made King their president. Their requests included that they be treated with civility by whites, for blacks to be hired as bus drivers, and that seating be on a first-come-first-served basis. The boycott continued until they received an answer to their demands.

It was six months later, on June 5, 1956, that a federal court in Montgomery came to the conclusion that a law calling for segregation on buses based on race violated the Fourteenth Amendment. That same year, the U.S. Supreme Court heard the ruling and gave its approval of the court’s decision. The boycott ended after 381 days. His participation in this event marked the beginning of King’s recognition in the fight for racial justice.

Opponents tried to fight against bus integration, however, causing much violence. In early 1957, snipers began to shoot at buses, and bombs were placed at black churches and the homes of well-known black leaders, including King’s. The bomb crimes were traced back to the white supremacist group, the Ku Klux Klan, and several members were arrested, resulting in a mostly peaceful environment.

In 1957, King helped other civil rights leaders form the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Based in Atlanta, Georgia, the SCLC had the mission to work with local organizations that fought for racial equality. The organization spread the message of the fight for civil rights, but encouraged non-violence, which was highly believed in by King, in the process.

With the establishment of the SCLC, King was able to spread his message of equality to a much larger audience, even taking a trip to India. He moved back to Atlanta in 1960, where he joined his father as a pastor at a church and continued to focus on the civil rights movement.

On April 12, 1963, King took a trip to Birmingham, Alabama, where he and others protested the harsh treatments of blacks in the area. A court had recently released the decision that a permit was required for public gatherings to take place. King bravely went on with the protest despite this, resulting in the arrests of him and many others. Unfortunately, this was not the first time King had been arrested.

King was not allowed to have contact with his lawyers or wife when he was first placed in jail. It was only when President John F. Kennedy, who was days away from being elected, got involved that King was released on April 20.

King did not let being confined in a cell stop him from sharing his message. It was here he wrote his famous Letter from Birmingham Jail. The letter was eventually published all over the United States, sharing King’s message of equality and non-violence:

“You may well ask: ‘Why direct action? Why sit-ins, marches and so forth? Isn’t negotiation a better path?” he wrote. “You are quite right in calling for negotiation. Indeed, this is the very purpose of direct action. Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue.”

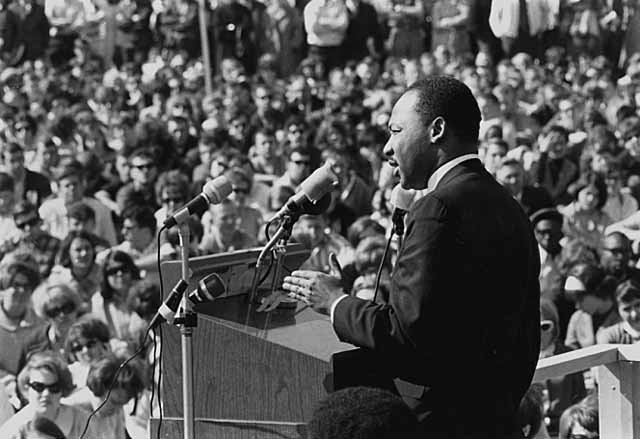

On Aug. 28, 1963, King and the SCLC took part in the March on Washington, where thousands gathered together by the Lincoln Memorial to protest racial inequality. Here, King gave the famous speech, “I Have a Dream,” where he talked about his dream, the dream of an end of racial inequality.

As time went on, the efforts of King and many others showed results. In 1964, the Civil Rights Act was passed, calling for integration in public and outlawing employee discrimination. The same year, King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

King continued his efforts for full equality of blacks over the next several years. In 1965, he took part in the Selma to Montgomery March for blacks to be able to vote in states that would not allow it, even though the Civil Rights Act prohibited this discrimination. Later that year, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed, allowing all blacks to vote without having to take tests, which some states had been forcing.

On April 3, 1968, King went to Memphis, Tennessee, and gave what would be his last speech, “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop.” The next day, he was sadly shot and killed while standing on the balcony of his hotel. He was only 39-years-old.

King left behind an incredible legacy. His peaceful efforts to bring racial equality to the United States and the world have been remembered for decades. His life and achievements continue to be a significant part of history to this day.

Rebekah Davidson

Intern