In an age where sci-fi and fantasy has taken inclusivity to new heights, it can be hard to imagine things being any different. We can forget, thanks to riches that brim off our bookshelves, of the pioneers that helped make the current golden age of speculative fiction possible. There are, of course, the more famous examples of Octavia E. Butler and Leigh Brackett. Less renowned but no less beloved by those that knew him or his work, is Charles R. Saunders.

To his fans he’s the genius credited with inventing Sword and Soul fiction, a sub-genre of Sword and Sorcery tales. But to his friends he was that and more: activist, passionate lover of sci-fi and fantasy, innovator, and a good soul. Fitting then, that part of his legacy includes a body of work that accomplished a lifelong dream.

Among the many luminaries lucky enough to have known the mind behind classics like “Imaro” was World Fantasy Award-winning author Charles de Lint. He was more than happy to talk to The Clarion about his late friend, who died in 2020.

He left us with many finished works, rich in background, sometimes brutal, sometimes tender, but always utterly absorbing

Charles de Lint

“I first met Charles (Saunders) in the mid-seventies, not as a writer but as a friend of a friend. He was kind enough to take me under his wing and introduce me to the world of ‘zines of which I had not experience of whatsoever. We remained friends for the entire time he lived in Ottawa, a friendship we kept up when he moved to Halifax,” his compatriot de Lint said.

The lifelong friendship that blossomed between them would see them link up whenever de Lint visited Halifax, be it for book tours or festivals. In a time before internet, much of their intervening correspondence was by letter. He recalls the large network of friends the late author had when they first met and the many interests that drove him.

“Charles was very compartmentalized. He had his fantasy friends, his boxing friends, his work friends from Algonquin. I was one of his fantasy friends and he was happy to talk about any aspect of the genre. It wasn’t until he moved to Halifax that his letters started to include elements of other parts of his life, in particular his activism,” de Lint added.

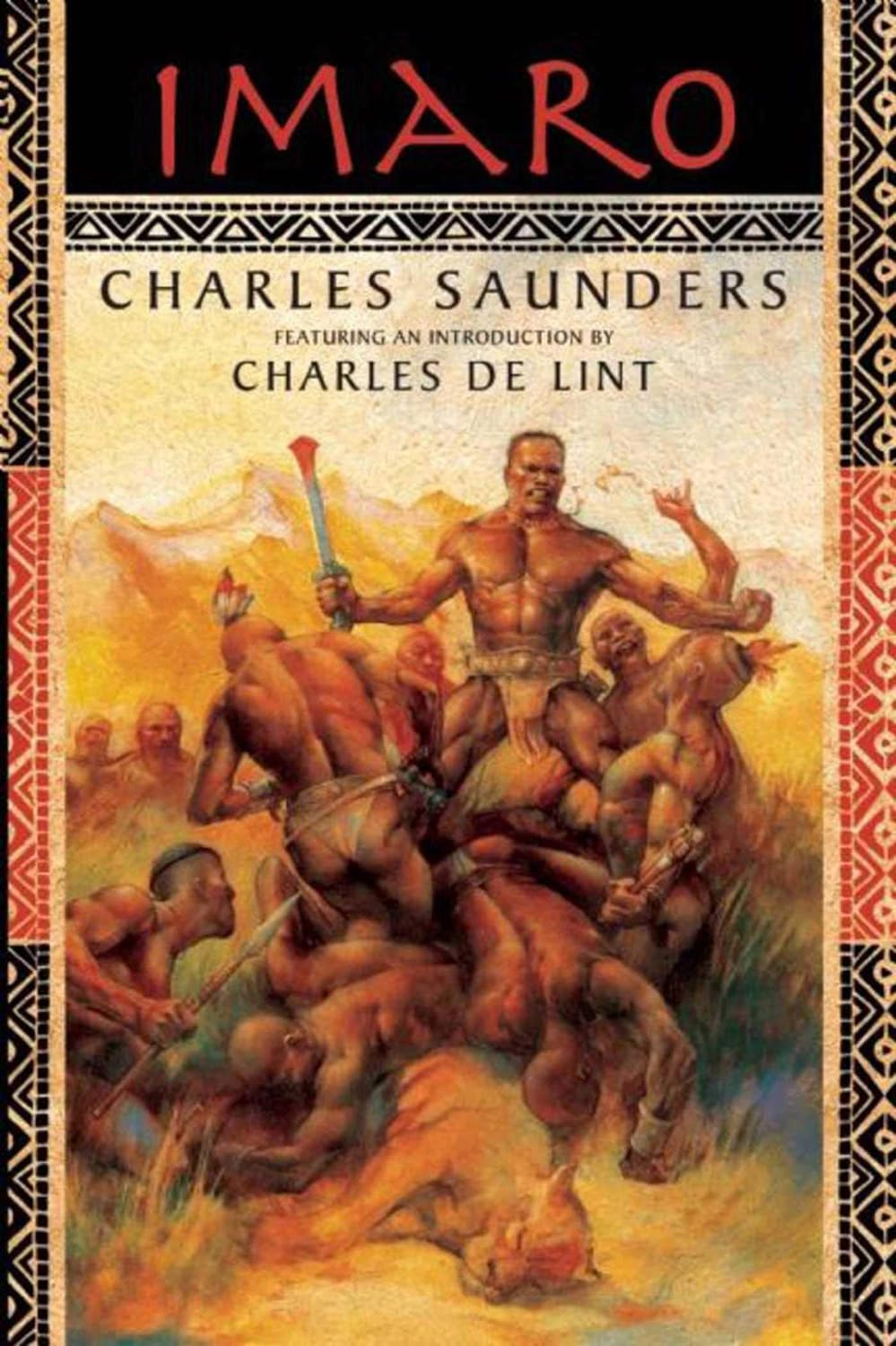

That Charles R. Saunders was a man of many interests is easy to tell from a quick look at his body of work. Going past the wonderfully old-school covers of battle scenes and muscular heroes takes you into an amalgamation of the many things he loved. Most importantly, however, is the sheer quality of his work which has led many to call him a natural storyteller.

This cover channels Saunders’ love for other pulp classics. Photo Credit: DAW

“Like Robert E. Howard, who was a big influence on his early work, when you read one of Charles’ stories, its impossible to put down until you get to the end. His writing was so vigorous and certainly more nuanced than Howard’s. And although Charles wrote fantasy it was based on the real histories, folklore and mythology of Africa. I learned so much from him about it all,” de Lint said.

According to de Lint, his late friend was galvanized to stories inspired by Africa. A love of Howard and other early pulp writers helped drive the creation of “Imaro,” perhaps his most famous work. The Canadian author wanted to do for African culture what Conan the Barbarian, Soloman Kane, and other stories did for European-inspired fantasy.

“There’s a whole generation of young writers creating new ‘Soul and Sorcery’ stories, influenced by Charles’s work. It might remain a fringe interest, but even back in the day the Sword and Sorcery and Heroic Fantasy we were reading was on the fringes of the genre,” de Lint explained. It’s easy to see how a writer like Saunders would thrive in today’s more open environment.

“Today fantasy, sf and horror is written from many cultural viewpoints, which is a wonderful thing. But Charles was one of the first to step away from what Howard, Tolkien and other European writers were doing, striking out on his own, borrowing elements of what had come before, yes, but taking them into an entirely new (at the time) direction. I’m sure we would have gotten there eventually, but he was at the vanguard, showing us the way. I hope that will be recognized and remembered,” said de Lint.

“He was first and foremost a storyteller, a modern griot, if you will, to borrow an African term from his work. If you like secondary world fantasy and have grown tired of the mock-medieval, Eurocentric thrust that permeates so many of them, I think you’ll be delighted to find actual new worlds to explore in his work, based on the histories of Africa,” de Lint added.

Beyond just being an incredible writer and visionary, those lucky enough to have known him will remember the man behind “Imaro” for so much more.

De Lint said, “I write to find out what happens next in whatever I’m working on but Charles always needed to have the whole story in his mind before actually writing. I spent many an hour listening to him relate his stories, many of which, unfortunately, never made it to paper. But he left us with many finished works, rich in background, sometimes brutal, sometimes tender, but always utterly absorbing.”

Ismael David Mujahid, Executive Editor

(Featured Image from Night Shade)