Last month I wrote on the many different foods we consume during the holiday season and their origins, and now it’s time for round two. Let’s take a look at some of the foods synonymous with the holidays.

Feijoada

One of the unique qualities of Kwanzaa is the vast variety of foods that are made for the celebration of African heritage, unity and culture. During the early years of the holiday in the 60s, the focus was on strictly traditional African dishes. Today this has changed, and pretty much any dish that has its roots in the geography of the African diaspora is fair game.

Feijoada, the national dish of Brazil, is a stew consisting of black beans, a variety of salted pork or beef products, such as pork trimmings (ears, tail, feet), bacon, smoked pork ribs and at least two types of smoked sausage and jerked beef (loin and tongue).

In some regions of the area, like Bahia and Sergipe, vegetables such as cabbage, kale, potatoes, carrots, okra, pumpkin, chayote and sometimes bananas are added at the end of cooking, so that the vapors of the beans and meat contribute to the veggies’ flavor.

Related Articles

- Here’s Henry: The Holly Jolly Food Traditions of the Holidays

- Reverend Janglebones’ Soapbox: Food For Thought

It leaves a strong, salty taste dominated by the flavors of black beans and whatever meat was in the stew.

Traditionally it is served with white rice and oranges on Saturday or Sunday afternoons and is intended to be a leisurely midday meal, meant to be enjoyed throughout the day and not eaten under rushed circumstances.

Legend has it that the origins of the dish come from Brazil’s history with slavery, as slaves would craft the dish out of pork leftovers given to them from their households, as pig feet, ears and tails were seen as unfit for a master or his family. Scholars dispute this and trace it back to Brazil’s cultivation of black beans, which were cheap and easy to maintain.

Accras

Also known as Caribbean Fritters, Accras are essentially fish cakes made from fish, shrimp, peas or beans that have been cured in salt and dried until every last ounce of moisture has been drawn from it. It is put in a batter and has fresh herbs with hot pepper added as well.

The islands that serve the dish vary their recipe depending on the amount of flour used in the batter and if any baking powder is used. No two locations make it the same way. Accras are often served as appetizers or sides in larger meals with a wide range of sauces and toppings available.

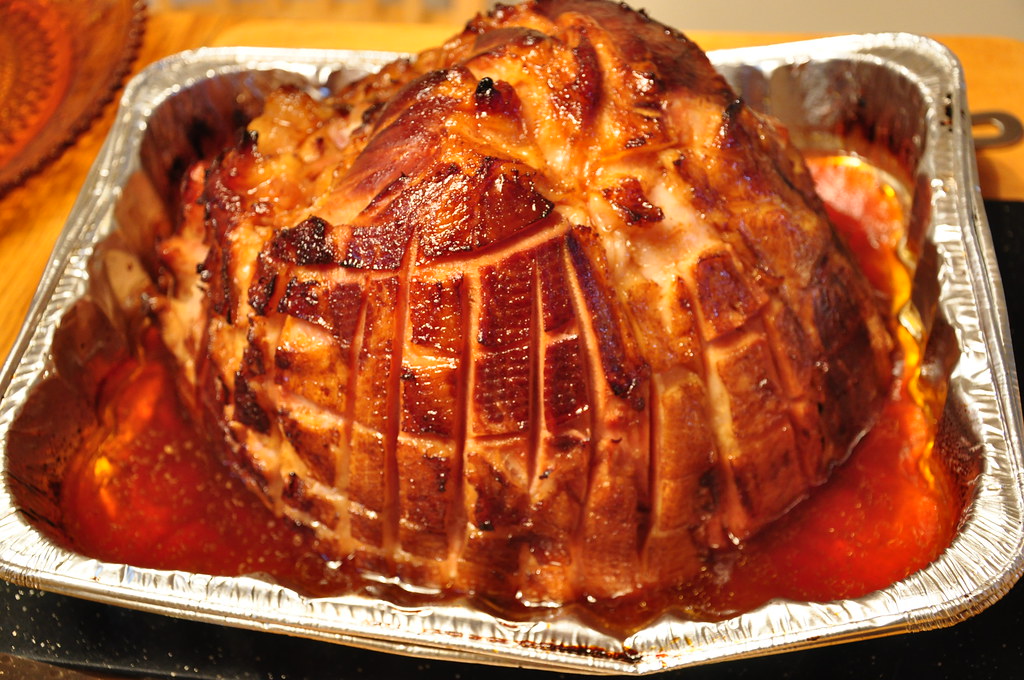

Christmas Ham

The centerpiece of the Christmas dinner can vary wildly. Some people bust out the turkey and party like it’s December, others feast on a leg of lamb, indulge in a pasta dish or, if you’re like my crazy family that spends Christmas in a condo in Florida, you gorge yourself at an Asian buffet, go home and fall asleep while watching “National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation.”

Yet the popular option is whipping up an old reliable Christmas Ham. The pig has a spot in winter celebrations dating back many many centuries.

Norse cultures would eat wild boar as a tribute to Freyr, the god of fertility, prosperity and fair weather. Pagan cultures ate ham during their Yuletide celebrations as well, in a festival honoring the mythical Wild Hunt and praying for fertility. When they converted to Christianity, the porcine meal honored St. Steven, whose feast day is Dec. 26.

When Pope Julius I established Dec. 25 as a day to celebrate the birth of Jesus Christ due to the abundance of winter solstice celebrations (as Christmas is not actually Jesus’s birthday), the consumption of ham was one of the many traditions of old that stuck. I prefer Rum Ham myself.

Yorkshire Pudding

A hugely popular British dish whose namesake comes from a historic county of Northen England and is the largest in the United Kingdom, Yorkshire pudding is served with roast beef on Sunday dinners throughout Europe.

Since the 18th century, the dish has been featured on many a Christmas menu, though it hasn’t caught on as much in the states.

However, the baked pudding’s origins are shrouded in mystery, and no one really knows how it was first made, or survived throughout the years prior to its inclusion in a book called “The Whole Duty of a Woman” in 1737.

Ten years later, the dish became one of Britain’s favorites when it was featured in famous food writer Hannah Glasse’s “The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy.”

Following the wars of the early 1900s, the pudding’s popularity rose again, with the dish being mass-produced worldwide and serving as a dinner staple in the UK, even if no one knows how this mix of flour, eggs, milk and salt was concocted.

“It is an exceeding[ly] good pudding, the gravy of the meat eats well with it,” Glasse states.

Come back next week as we look at some of the most famous Christmas desserts and how they came to be.

Henry Wolski

Associate Editor