It’s time to address the prevalence of black “torture porn” within the film and print industry.

Over the past few decades, Hollywood has been (rightly) criticized for its over-the-top, hackneyed and ridiculously stereotypical portrayal of Black Americans in countless films and television shows since the first quarter of the twentieth century.

The examples are numerous. 1915’s “The Birth of a Nation” portrayed black men, women and children as mindless, id-driven savages while the Ku Klux Klan were portrayed as brave, upstanding citizens. President Woodrow Wilson even held a special screening of the hit film at the White House.

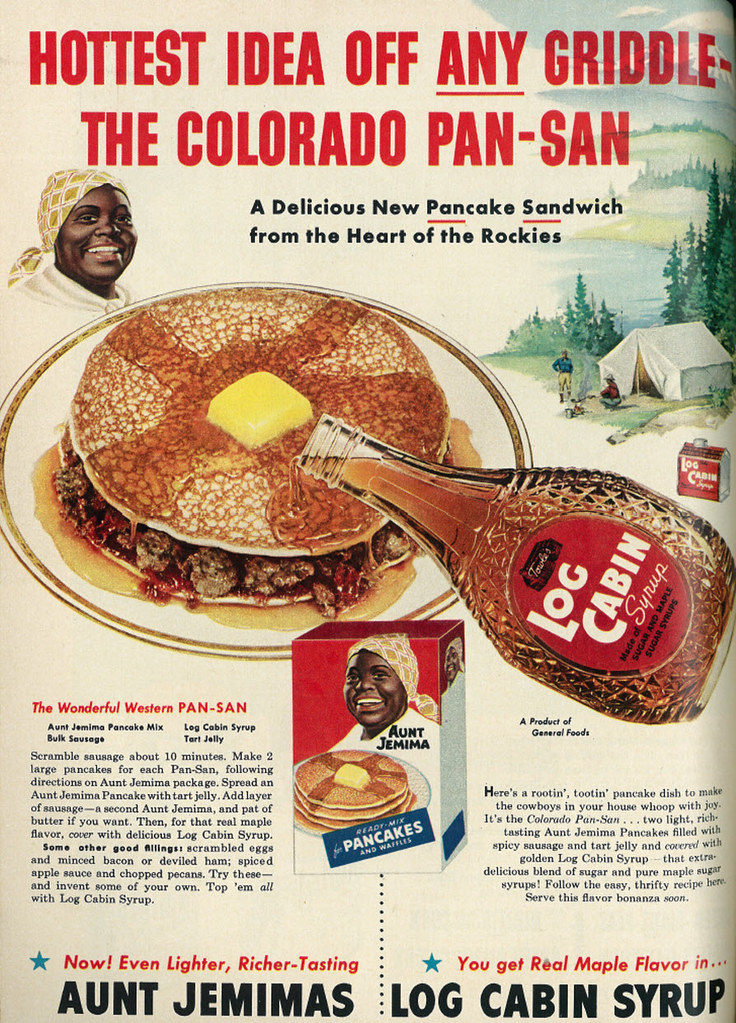

Actress Hattie McDaniel’s role of ‘Mammy’ in 1939’s “Gone With the Wind,” in which McDaniel played the trope of the heavy-set, scarf-wearing, loud-mouthed Black nanny, whose image closely resembles that of the infamous “Aunt Jemima” character, complete with the same jive-talk manner of speaking used on the latter’s early advertisements.

1974’s “Good Times” broadcast the character of “J.J. Evans” (played by Jimmie Walker), whose bug-eyed Al Jolson-esque facial expressions and signature catchphrase (“Dy-no-mite!”) made him and “Good Times” itself a frequent guest in living rooms all across America during the show’s six season run.

Morgan Freeman, in 1989’s “Driving Miss Daisy,” assumed the role of Hoke Colburn, a grinning, doting, mild-mannered chauffeur for an elderly, wealthy white woman—playing what can be seen as a male version of the ‘Mammy’ trope.

2004’s “Soul Plane” turned the dial up to eleven, with seemingly every black stereotype that the average “National Review” reader can conjure up in their imagination broadcast on the big-screen (fried chicken, forty ounces, gold chains, 3XL t-shirts, gold grills, blunts and twerking). Looking back on it now, this was clearly an act of satire—but satire can be easily misconstrued.

Then, in the early phases of the Obama administration, a big shift happened in the realms of Hollywood and the print media.

Related Article:

With the minstrel-style tropes used in representations of Black Americans throughout the twentieth century being ripped apart by critics and nearly phased out of modern media (for the most part), the themes attributed to black people in films switched from buffoonery and joviality to violence and despair.

The first instance of this was 2009’s “Precious,” a film directed and produced by Lee Daniels and which starred actress/comedian Mo’Nique, earning her a Golden Globe, a SAG award, a BAFTA (The British Academy of Film and Television Arts) award and an Oscar.

The film was highly-acclaimed and serves as the progenitor of the current narrative that peppers the landscape of modern-day black film and television: Pain.

Starring lead actress Gabourey Sidibe as an illiterate, poverty-stricken teenaged girl named Claireece ‘Precious’ Jones, this film wrote the blueprint for what I see as the “Black Pain Equals Financial Gain” marketing gimmick.

The dialogue is sparse to a degree, as most of the film unfolds by way of trauma after trauma: Precious is shoved to the ground as a group of neighborhood boys mock her, physically and emotionally abused by her mother, has frequent nightmares about the times her father raped and impregnated her, learns that she’s HIV-positive and ultimately views herself as worthless.

The movie ends on a pretty flat note, with Precious eventually breaking away from the grips of her tyrannical mother by moving into a halfway house with her two children and planning to complete a GED test.

Curiously enough, the film features an early scene in which Precious steals a bucket of chicken from a restaurant and eats the entire thing while fleeing down the street as the restaurant’s cashier yells at her. I guess Daniels and his staff just couldn’t resist harkening back to an age-old trope.

From beginning to end, “Precious” is little more than an exercise in visualized sadism-by-proxy in the eyes of keen observers. Hollywood audiences, however, upheld and cherished the film.

Two years later, 2011’s “The Help” made another big impact on audiences, this time in the form of two black maids in 1960s America tasked with caring for the households and children of white bourgeois socialites.

The film is far less heavy on the “pain” aspect—with the two maids facing discrimination more in the vein of head-shaking ignorance and chuckle-worthy silliness—but alas, the “Black Pain Equals Financial Gain” formula is still very clear throughout the film.

The women are mistreated at the beginning (like in “Precious”); halfway through, a “white savior” comes to their aid (similar to the characters played by Mariah Carey and Paula Patton in “Precious,” with light skin in place of white skin); and then the film ends with both women being treated like the human beings that they truly are (again, just like “Precious.” See the trend?).

2013 gave us “The Butler,” also written and directed by Daniels. This film is really no different than “The Help”; all you have to do is swap the two black maids with one black butler in the White House (Cecil Gaines, played by Forest Whitaker) who faces discrimination and with the aid of yet another “savior” earns a pay raise and respect after a decade of servitude.

And now, after having tested the waters with lighter forms of racism and racial injustice, Hollywood has recently decided to go for the jugular vein of the “woke” blue-checkmark Twitter brigade.

“12 Years a Slave.” “Selma.” “Detroit.” “Free State of Jones.” “13th.” “Moonlight.” All stories of black pain and suffering that were heavily marketed and dispersed to American audiences.

Supporters of films such as these like to stress that they are important because they “tell important stories,” a similar sentiment that I heard Charlamagne tha God, co-host of popular nationally syndicated radio show “The Breakfast Club” and New York Times best-selling author, make a few weeks ago on his podcast “The Brilliant Idiots” with co-host Andrew Schultz.

His remark was in reference to filmmaker Ava Duvernay’s latest project “When They See Us,” which details the story of the “Central Park Five,” five inner-city black kids from New York who were falsely imprisoned and railroaded by the American justice system.

On a surface level, I agree with the stances of Charlamagne and many others who assert that stories of real-life accounts of black plight should be told. However, “surface level” appears to be where most people are kept in while projects like these receive acclaim and accolades from critics and everyday people.

The “surface level” that I’m speaking of is how after the tweets have begun to taper off and the buzz has died down, the gearshift of the American racial/socioeconomic conscious remains mostly stuck in neutral.

After the watch parties, post-film discussions and breakdowns, nothing more is done.

Instead, awards and recognition are doled out—along with a hefty profit for those involved in the project’s creation.

The hard truth about these sorts of films, both the ones fictional and historically accurate, is that they mostly entertain rather than educate.

These fictional and real-life accounts of black pain, misery and misfortune have sadly become somewhat of a money-grab for filmmakers, writers and producers alike.

It seems that films of this nature are churned out every few months, make a big splash and are quickly forgotten about—rather than used as tools to educate oneself and fight for blood-stained revolution instead of sugar-coated reformation.

Audiences are inspired to retweet rather than group meet, view rather than do and analyze rather than organize.

Even in the print world, a similar trend is seen, as countless authors have waxed poetically about Black American struggles. While offering no actual solutions.

At the public library that I frequent, these types of books line the shelves in droves.

Some of the recent books that I recall are author/intellectual Michael Eric Dyson’s “What Truth Sounds Like,” “How Not to Get Shot: And Other Advice From White People,” by comedian D.L. Hughley and the books “Between the World and Me” and “We Were Eight Years in Power” by Ta-Nehisi Coates.

Much like the films that I criticized earlier, these works—and others like them—aim to entertain, not to revolutionize. And while I consider Ta-Nehisi Coates to be a phenomenal writer, I’d say that he’s the greatest offender of this cliche in print, with Lee Daniels serving as his pseudo-Shakespearean Hollywood counterpart.

Coates’ “Between the World and Me” was beautifully written, but the underlying messages throughout this work and his others—especially in the case of “We Were Eight Years in Power”—reek of the same pessimism, vague cries for neoliberal acceptance and Obama worship that a certain black intellectual has taken note of.

Though I find Coates to be a great writer, his work seems all-too geared for upper-middle class liberals who support various notions of “equality” but recoil in horror at notions that they deem “far-left.”

Thankfully, Hollywood has calmed down on slave movies as of late, but I worry that the uptick in documentaries featuring real-life accounts of black injustice will lead to yet more bourgeois discussions and fancy film screenings—with the work toward real, concrete and material action against the very system being complained about relegated to the background.

Quinton Bradley

Intern