I promised in the waning sentences of the last article that we’d be focusing on an atypical “horror film” this week. I also promised that it’d be a sort of satire on one of the genre’s longest-running staples. So, without further adieu, I’d like to talk to you all about the comedic brilliance of “What We Do in the Shadows.”

The film itself is rather new, releasing in 2014 at the Sundance Film Festival and in New Zealand, the filmmakers and stars Taika Waititi and Jemaine Clement’s, native homeland. It has since spawned a TV show that premiered this past spring on FX.

The movie itself kind of slipped under the radar despite the somewhat cult status of the duos’ previous work. Jemaine Clement has starred, provided his voice and had various bit parts in several movies and TV shows over the course of his career. But he is most famous for being one part of the comedy duo “Flight of the Conchords,” which spawned a TV show that ran on HBO for two seasons back in the early aughts.

Waititi got his start directing several episodes of the aforementioned show and wrote and directed the cult film “Eagle vs Shark,” which starred Clement.

If you haven’t seen it, I cannot recommend it enough. It’s basically a New Zealand “Napoleon Dynamite” but WAY funnier and filled with a hell of a lot more emotion. I dare you not to love the two main characters by the film’s end.

Waititi has since directed one of the best films in the entire MCU, and definitely the best Thor film, in “Thor: Ragnarok.” He also provided the voice for fan-favorite character Korg.

“What We Do in the Shadows” on its surface sounds like a terrible, terrible idea. A mockumentary on vampires living in New Zealand. It should be rife with cringe-worthy jokes and satire so stale it makes Mel Brooks’ “Dracula: Dead and Loving it” look revolutionary (nothing against the genius of Mel Brooks as we’ll eventually get to one of his films, which is, in my opinion, one of the greatest comedies of all-time, but many of his later films lacked some of the brilliance of his early work).

The film itself takes on one of the oldest bastions of the horror genre: the vampire. Bram Stoker’s “Dracula,” the book that inserted the vampire mythos into the Western world’s consciousness debuted just a hundred years after the first “horror” novel. And though it wasn’t the first book about vampires, it certainly is the most popular, and still among one of the first and most influential stories within the genre.

Related Articles:

Though, despite it taking on a tired, often ridiculed subject, the film is genuinely brilliant and funny. In fact, despite being a movie that takes on a horror subject so old it dates back to the early days of horror fiction, it still is genuinely good satire on a genre that has pretty much run its course with the “Twilight” books and their “sparkly vampires.”

Much in the vein of 2004’s “Shaun of the Dead,” the film takes on a tired staple of the genre and injects new life into it through satire. Also, like “Shaun of the Dead” the movie grounds its biting satire of its desired target in genuine humanity. In the film, most of the jokes are not about how vampires are lame or tired but instead about the ways in which disparate people get along in a community. The four tenants of the New Zealand flat bicker and argue much in the same way three tenants would bicker and argue if it were a sitcom.

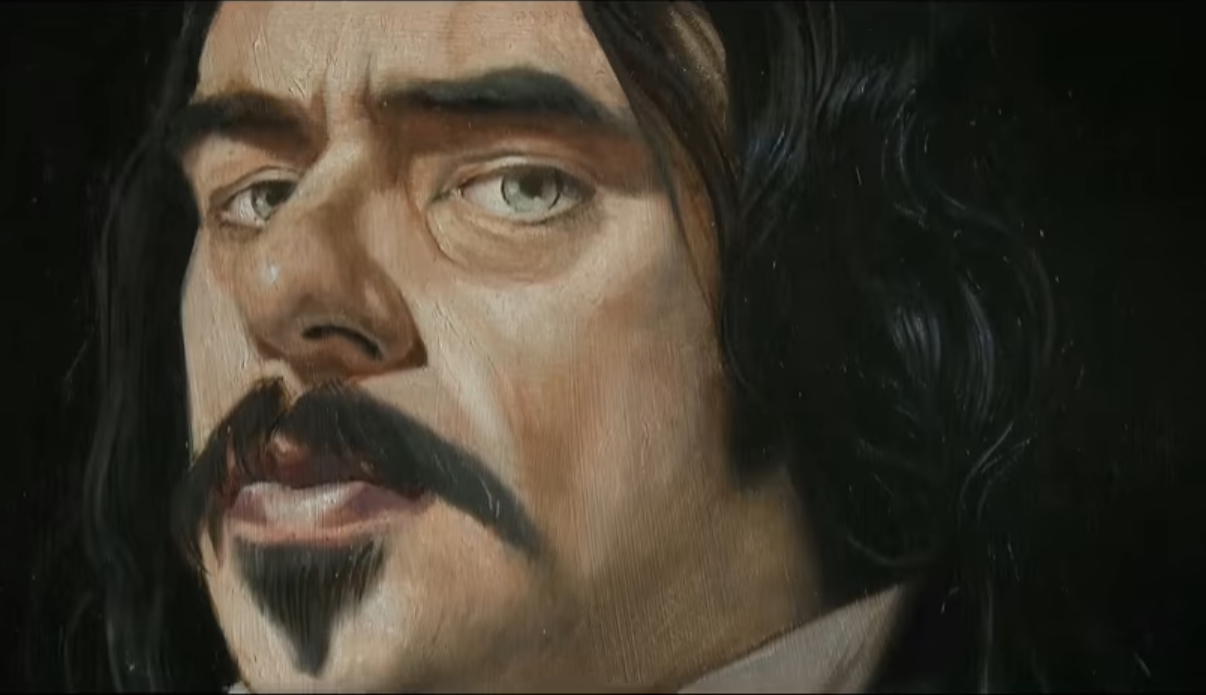

The tenants, Viago played by the film’s director, Vladislav the Poker played by Clement, Deacon and Petyr all live and exist much in the same way that most un-undead do. They bicker and argue about chores. They go out for a night on the town–the scene in which they get ready being one of the film’s best montages, and they try their best to get along, despite their varying differences.

Akin to “Shaun of the Dead” the film takes these iconic horror characters and makes them as domestic and as ubiquitous as they are in our everyday lives. The horror from zombies removed to such a degree that they’ve spent the better part of the past few decades as fodder for video games and TV shows that apparently a lot of people watch, but that nobody really likes anymore.

The same has happened to vampires. Being reduced and melted down to their oversexualized elements to play a part in quasi-young adult romance novels. In other words, the fear is gone.

Though, the movie is a satire of the genre’s tired old routine, the reason why the film works and doesn’t just feel like a bad “Family Guy” episode, more worried about the amount of connections it can make rather than whether the connections have anything to say, is because the movie doesn’t lean too heavily into the satire.

Instead, it plays like a stereotypical mockumentary. It’s no different from any of Christopher Guest’s films (pioneer of the mockumentary genre who practically invented it with movies like “This is Spinal Tap” and “Waiting for Guffman”) in that it is just about people, living their lives.

The comedy and the satire resides then underneath all of that. We are presented with characters that we’re invested in because, much like sitcoms that work, they’re people we want to spend time with.

We care because they feel like people (despite being undead vampires) who we feel a connection for. Which is, strangely, a rather new spin on an old theme of the genre. Because, after all, it is the fear that we might become monsters that has always been the fear of the vampire.

As the vampire mythos is rooted in Eastern European lore; a way of explaining the effects of what was then referred to as consumption, but that we typically refer to as tuberculosis.

Slavic people in Eastern Europe then invented the vampire, a beast that wakes from the dead and consumes the living, as a way to explain something they couldn’t understand. The greatest fear being to become one of the beast’s own and to then be, like him, a monster.

The film takes this theme and turns it around. Which makes sense because if anybody has digested vampire films or literature since then, it does seem pretty rad to be a vampire, other than that whole being afraid of sunlight thing. Unless that’s your thing.

But Vladislav, Viago and the rest all seem to enjoy it, and when a young New Zealander joins them in their flat after a night of “basghetti,” himself being transformed into a vampire by Petyr, he seems to enjoy it, too.

Sure, they have some problems at first, but by the film’s end, the message sinks in that these are simply people, trying their best to get along and live in a world that they hardly understand. Who can’t say that’s anything but a universal feeling.

Beyond that, beyond what the film takes apart and rebuilds from a genre that’s almost as old as the larger genre of horror in general, is that it’s simply a great, infinitely creative film by an infinitely creative filmmaker.

And, as a side note, I once showed the film to a friend’s daughter and it became her favorite movie. So, there’s that, too.

Next time I’ll move further away from the genre and take a look at an actual documentary about an overlooked and nearly forgotten horror director who never was. It’ll be an American dream come untrue.

Richard Foltz

Managing Editor