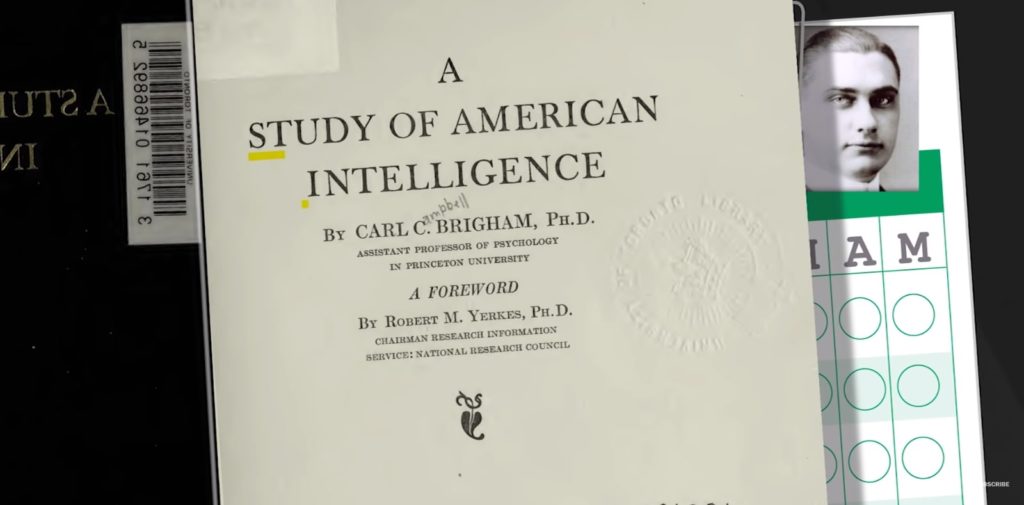

The Scholastic Aptitude Test, better known as the SAT, was first hypothesized by a World War I psychologist named Carl Brigham, with the intent of measuring intelligence. Yet his initial findings, published in 1923, “A Study of American Intelligence” had some pretty dated results that may still leave a nasty mark on today’s education system.

Of the breakdown into nationalities of descent, the study concluded that white people of English, Scottish or Dutch descent to be at the top, while recent immigrants from Poland, Italy and African Americans were at the bottom.

In his book, “The Racist Origins of the SAT,” historian and author Gil Troy calls Brigham a “Pilgrim-pedigreed, eugenics-blinded bigot,” pointing out the problems with his testing, namely that they were biased towards English speakers and how some test-takers weren’t allowed access to adequate education.

Despite this, the SAT is still the norm for most college bound high school students, a problem that is further exacerbated on the family median income ladder by the boutique SAT test-prep market.

Companies like Kaplan, Princeton Review and Prepscholar offer test-prep for prospective college students but at a hefty price, with some of the cheapest being several hundreds of dollars.

This becomes problematic when you look at SAT scores in comparison to family income, wherein students whose families make $20,000 annually score an average of 890 and students whose parents make over $200,000 score an average of 1150, this according to College Board, a non-profit out of New York that works on expanding access to higher education.

“It was drummed into us that the key to getting the career of our dreams was getting into college,” said Max Castleman, Bowling Green State University graduate, who grew up in an upper-middle-class neighborhood outside of Boston, Massachusetts. “And the only way to get into the college we wanted was to get good SAT scores. The easiest way to do that was to pay for an expensive tutoring program, since our weirdly focused standardized test-based education had not adequately prepared us for the challenges of the test.”

“While I was in public school, in the wake of the ‘No Child Left Behind Act,’ standardized testing took on a new level of importance, and so much time was spent training us for these specific questions on these specific tests that establishing a ‘general knowledge’ of topics like mathematics and history was de-emphasized,” added Castleman, noting the emphasis for testing, rather than learning.

“By the time we took the SAT the information we had was so specific that a good portion of the test went over many of our heads. Coming from a wealthy school district, many of my peers were able to use expensive prep programs, and the school chipped in by offering optional seminars of its own. Those who could not afford these programs, myself included, were at a huge disadvantage when taking the test, and I can imagine that this issue was greatly exacerbated for those who spoke English as a second language.”

Related Articles by This Writer.

- New Studies Suggest Different Narratives Concerning Undocumented Immigrants.

- Work Discrimination Set Against The Backdrop of Coming Out Week.

This emphasis on college-first, test-oriented education has also had an effect on trade jobs as well. According to a PBS article in 2017, more than half of tradespeople were 45 or older in 2012.

Young people for the past couple of decades just aren’t being given the information, instead shifting their ideal future to college-oriented rather than vocational and trades jobs.

The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), the federal statistics keeper for the Department of Education shows that only 8 % of undergraduates are training for vocational jobs.

And despite there being 30 million jobs in the trade industry that pay $55,000 or more, according to the aforementioned PBS article, these jobs are statistically only being filled by kids from the lowest rung of the economic ladder.

The big problem here is that this chain regurgitates the inequality in the United States education system, wherein, according to research conducted by Stanford researcher Raj Chetty, the kids who go to the most prestigious colleges in America come from families with median incomes of $171,000, students who went to selective public colleges come from families that earned $87,000 and kids who went to community college come from families that earned $67,000.

When those kids exit school, those who went to the most prestigious colleges earned at least $80,000 by their early thirties and those who went to other universities or community colleges earned half or less than that by their early thirties.

“I think the idea that I always had growing up was that those big, prestigious colleges weren’t ever a place I could go to,” said Noah Noble, Miami Valley Career Technology Center graduate. “Not due to anything but that it is financially and otherwise insurmountable and by extension, I felt like the types of jobs that those universities afford people would always be beyond my reach.”

Richard Foltz

Executive Editor