Sinclair will be showing “Resilience,” a movie about childhood trauma and its effects as a part of their Sinclair Talks series on Wednesday, Feb. 26 at 11 a.m. on the Building 8 Stage. The film will feature a conversation after the movie with Sinclair’s Mental Health and Addiction Services Chairperson and Associate Professor, Gwendolyn Helton.

The movie is an hour-long documentary about Adverse Childhood Experiences (also known as ACEs) focusing on the research of Robert Anda, an epidemiologist who has worked with the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Vincent Felitti, the former chief of preventive medicine at Kaiser Permanente in San Diego. Their findings — that certain risk factors, such as growing up around physical, sexual or substance abuse, have a strong correlation with major health problems in adulthood is a major theme in the documentary’s hour-long runtime.

With mental health being far greater a part of the national conversation, Sinclair wants to open a dialogue with students and faculty about the effects of trauma and how to work against those effects as students grow over the course of their time here at Sinclair.

The film’s trailer asserts that at least a quarter of the population has experienced some form of trauma but according to the CDC, those numbers, according to an article dated Dec. 2019, nearly 61% of people surveyed across 25 states have experienced at least one version of ACEs.

In other words, the number could be anywhere between a quarter to half of the U.S. population has experienced some form of childhood trauma.

According to an article titled, “The Impact of Poverty and Adverse Childhood Events on Child Health” by the Council on Community Pediatrics, dated Oct. 24, 2016, the adverse effects of ACEs go well beyond an individual problem and into the realm of a societal problem.

According to the report, ACEs leave the individual more susceptible to homelessness, juvenile and criminal justice system involvement, poor academic achievement, as well as developmental delay, cognitive impairment, ADHD and often, leads to a drop in academic achievement.

A higher ACE score can even lead to an increase in risk for heart disease, diabetes, depression, suicidal ideation, PTSD, anxiety and a number of other adverse physical and mental conditions.

Trauma also has a physical effect on your brain, creating a bevy of problems with decision making, leaving people susceptible to bad decision making.

“Let’s say you become really upset with someone,” said Sinclair Psychology Professor Danielle Boone. “And you just want to let them have it. Your prefrontal cortex is what really reigns you in. Well, if you’ve been traumatized to the point where your prefrontal cortex has been affected then you’re not gonna have that little voice telling you, ‘Don’t do that.’ You’re going to act out in ways that are socially inappropriate.”

“Secondly we have the ACC, the anterior cingulate cortex,” continued Boone. “And this is your emotional regulation center. So, outbursts, as well as a likelihood of increased chances of addiction to substance abuse and reliance on unhealthy coping mechanisms.”

“Lastly, the amygdala, which controls your flight or fight response. It can swell as a result of trauma. Which means you stay in this prolonged stress response and so that’s why we see the increase in heart disease, blood pressure, stroke, cancer, stomach ulcers, diabetes and for traumatized individuals, it’s also thirteen times the chance of suicide.”

This becomes a bigger problem not just for the individual but for society as a whole, especially when you consider the adverse effects on a larger and growing scale.

“If you have all of these people and they’re at a greater risk for cancers and heart disease and stroke and COPD, it’s huge,” said Boone. “So think of all the billions and billions of healthcare costs that are going to this. The support isn’t there for trauma. They’re still viewing trauma as a problem for social workers to deal with.”

“A lot of this is about access to care… Certain populations just don’t have access to care or the best practitioners and so, then they’re not getting the same care as somebody who has privatized insurance, they just don’t have access to those practitioners, and so that can marginalize certain communities to where they’re even more at risk because they’re not seeing people who are trauma-informed practitioners.”

There is a scene in Resilience, according to The Guardian, in which a pediatrician cites a practice of bad-parenting that, to our modern perception, seems so utterly outdated as to be ridiculous.

“Parents used to smoke in the car with kids in the back and the windows rolled up,” says the pediatrician and it hits upon a failure in parenting so obvious to us now that at one time was seen as normalcy, the inference being that the poison we’re currently giving to our kids might seems as innocuous as cigarette smoke might’ve seemed to past generations.

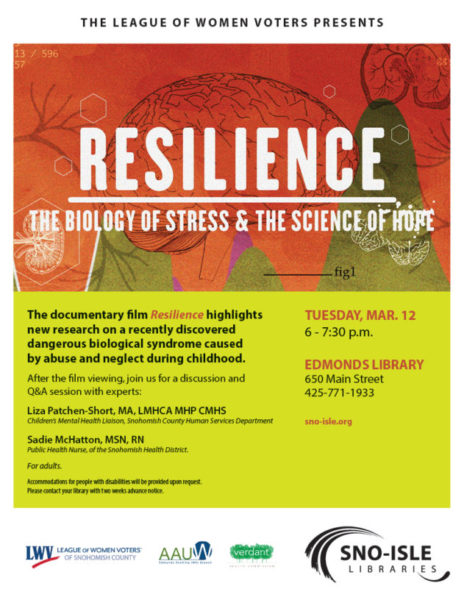

Despite this, there is hope, as the documentary’s slogan, “The biology of stress, the science of hope” asserts.

“The Facilitator’s Guide to ‘Resilience,’” a guide is given to accompany the screenings of the film says, “Resilience is a natural counter-weight to Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). The more resilient a child is, the more likely they are to deal with negative situations in a healthy way that won’t have prolonged and unfavorable outcomes. Resilience is not an innate characteristic, but rather is a skill that can be taught, learned and practiced. Everybody has the ability to become resilient when surrounded by the right environments and people.”

As famous kids television host, Fred Rogers, of “Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood” once put it:

“Anything that’s human is mentionable and anything that is mentionable can be more manageable. When we can talk about our feelings, they become less overwhelming, less upsetting and less scary.”

Richard Foltz,

Executive Editor