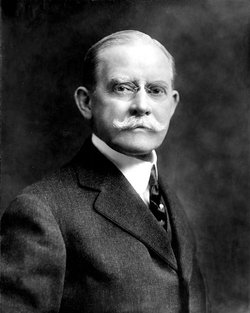

Last week on Gem City History we took a look at the devastating flood of 1913. One of the interesting parts of the story were the efforts made by John H. Patterson to help those affected by the storm as well as the journalists reporting on it. He is one of the biggest figures in Dayton history, so this time we’ll be taking a look at his life and what he did to propel the Gem City forward.

Patterson was born in Dayton on Dec. 13, 1844. He spent most of his youth working on his father’s sawmill before joining the union army in the American Civil War. He served for 100 days during the final stretch of the war. Following this, he graduated from Dartmouth College in 1867.

He then became a toll collector on the Miami and Erie Canals until 1870. After that he switched to the coal industry for 10 years, and served as manager of the Southern Ohio Coal and Iron Company.

Patterson’s next business venture was investing into the National Manufacturing Company in 1882. Two years later he bought the company out with his brother and formed the National Cash Register Company (NCR). He would spend the rest of his career there and forged his legacy with the company.

Patterson’s next business venture was investing into the National Manufacturing Company in 1882. Two years later he bought the company out with his brother and formed the National Cash Register Company (NCR). He would spend the rest of his career there and forged his legacy with the company.

One of his first actions was to implement aggressive marketing techniques to get store owners to buy the original mechanical cash register, invented by James Ritty in 1879.

At the time, cash registers were rare and an expensive machine that shopkeepers saw little value in. However, Patterson knew that the addition of cash registers would drastically decrease theft from stores. He sought to not only convince them to purchase his product, but to sell them on a business philosophy. This philosophy being “We progress through change.”

To accomplish this he created a sales team known as the American Selling Force. They worked on a standard sales script and set up demonstrations in hotels (away from distractions to potential buyers).

These included making a room depicting a store interior complete with real merchandise and real cash. Potential buyers would admit to losing money due to internal theft, and were shown many charts and diagrams as well as a demonstration of what the cash register could do to change their minds.

Another tactic Patterson implemented was what is now known as direct mail. To increase awareness and demand for the cash registers, he sent six pieces of mail a week for three weeks to a list of 5,000 potential customers, filled with information on the product. This also created more opportunities for international customers for NCR.

He also helped create the image of the modern salesman. NCR was one of the first businesses to offer commision and guaranteed territory to employees. His top sellers began rattling off the first canned sales pitch, and wore the most fashionable clothing and stayed at the nicest hotels to impress customers.

He also helped create the image of the modern salesman. NCR was one of the first businesses to offer commision and guaranteed territory to employees. His top sellers began rattling off the first canned sales pitch, and wore the most fashionable clothing and stayed at the nicest hotels to impress customers.

“Nothing denotes the gentleman more,” Patterson said, “than earnestness and politeness.”

Patterson then established the world’s first sales training school on the campus of the main NCR factory in Dayton. This is where he would teach salesmen the basics of the trade.

He coined a phrase for his service division that is still stuck with country. This phrase was “We Cannot Afford To Have A Single Dissatisfied Customer.”

NCR became a hugely successful business, and by 1914, they were producing 110,000 cash registers per year, with 30 percent of their orders being overseas customers.

Patterson was known for some eccentric personality traits, including being a health nut, trying out several different exercise and dieting regimens.

He passed his health beliefs and practices on to his staff, and instated routine weigh-ins for NCR employees every six months. He would do this to monitor their health, and issued free malted milk to those who were underweight.

He did this to increase productivity of his workers, as he believed that clean, attractive factories would lead to healthier, more productive employees.

Another trait Patterson became famous for was sometimes excessively firing people. He would fire them for trivial things such as if they couldn’t ride a horse properly. One NCR executive recalled returning to the facility from a business trip and seeing his desk and belongings laying on the lawn. He then watched a maintenance employee pour kerosene on them and light it on fire.

Another trait Patterson became famous for was sometimes excessively firing people. He would fire them for trivial things such as if they couldn’t ride a horse properly. One NCR executive recalled returning to the facility from a business trip and seeing his desk and belongings laying on the lawn. He then watched a maintenance employee pour kerosene on them and light it on fire.

Many of the prominent businessmen of the time were hired, trained and fired by Patterson. These included figures such as Thomas Watson Sr., who became the founder of IBM. Charles F. Kettering and Edward A. Deeds were among other notable figures trained at NCR.

Some historians regard the experience employees gained under Patterson as a rough equivalent of an MBA degree.

Yet Patterson did care about the well beings of his workers, and took measures to increase their quality of work.

A notable change he made was renovating the NCR manufacturing facilities after he purchased it. He replaced the walls with 80 percent glass so that work could be done in natural light. At this time, sweatshops were still commonly used in the U.S. He also removed debris, added ventilation and shielded dangerous equipment to protect employees.

He instituted lunchtime lectures so NCR employees would maintain a general interest in the world. These eventually took place in the NCR auditorium, and were built on the idea that employees needed to keep their minds active if they were going to remain productive.

In 1922, two million units were sold by the company. This was also the year that Patterson died. He is buried in Woodland Cemetery and didn’t leave behind a fortune to his name, due to the money put into social programs in the company.

In 1922, two million units were sold by the company. This was also the year that Patterson died. He is buried in Woodland Cemetery and didn’t leave behind a fortune to his name, due to the money put into social programs in the company.

He was quoted believing that “shrouds have no pockets.”

He left behind a legacy of starting several business practices that became commonplace to this day, such as the canned sales pitch, direct mail and the use of aggressive promotional techniques.

It was estimated that between 1910-1930, one-sixth of business executives in the U.S. were former NCR executives. He was later inducted into the Junior Achievement U.S. Business Hall of Fame in 1979.

NCR continued to flourish with Patterson’s son, Frederick Beck Patterson, at the helm. The company went public in 1925 with an issue of $55 million in stock. Through the years, the company adapted with the times and moved beyond cash registers, now making self-service kiosks, point-of-sale terminals, automated teller machines, check processing systems and barcode scanners.

The city was shocked in 2009 when NCR sold their Dayton properties and moved their headquarters to Georgia. NCR was the Gem City’s only Fortune 500 company at the time, and the decision to leave left many shocked and angered.

While NCR left Dayton, Patterson did not, and the impact of his work is still relevant today. He paved the way for many business executives and salesmen by creating innovative practices and techniques. He also strived to create an environment to keep his workers happy, healthy, engaged and productive.

This, and his efforts to use his company as a safe haven for those affected by the Flood of 1913, will keep him in the Dayton history books indefinitely as an example of a model citizen, who used his power and resources for the betterment of the community.

Henry Wolski

Executive Editor